News

-

, by NZDiver Admin NZDiver Philippines Trip – June 2025 Trip Report

Warm water, limestone islands and world-class diving made NZDiver’s Philippines trip unforgettable. From El Nido reefs to tunnel and night dives, Palawan delivered on every...

-

, by numero Access Essential Snorkelling Gear: The Ultimate NZ Summer Checklist (2026)

Getting the right essential snorkelling gear makes all the difference when you explore local reefs and coastlines this summer. While the warmer months are the...

-

, by NZDiver Admin Why Getting Your Dive Gear Serviced Matters

Regular servicing of your dive gear is essential for safety, reliability, and performance underwater. This article explains why servicing matters, which equipment needs attention, and...

-

, by NZDiver Admin Understanding Eels in Aotearoa

🐟 Species in New Zealand New Zealand freshwater eel fisheries are dominated by two native species: Longfin eels (Anguilla dieffenbachii) – larger, more prized, and...

-

, by numero Access Snorkelling in NZ: What Beginners Should Know About Gear, Safety & Local Conditions?

Snorkelling in NZ offers a simple, affordable way to explore the country’s underwater life, but for beginners, knowing where to start can feel confusing. New...

-

, by numero From Screen to Sea: Smarter Hunting and Fishing in NZ

Every Kiwi fisher knows the thrill of heading out before dawn, hoping the fish will be biting. You load up the bait, cast your line,...

-

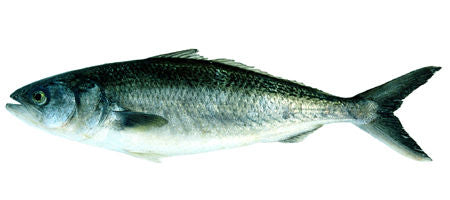

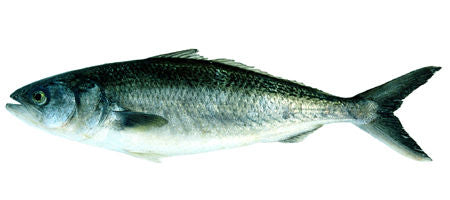

, by NZDiver Admin Kahawai – How to Catch Them

Kahawai are one of New Zealand’s most exciting and accessible inshore sportfish. Found everywhere from surf beaches to river mouths, they offer fast, surface-feeding action...

-

, by Joseph Dunnig Puerto Galera Dive Trip 2026 – NZDiver Holiday with Verde Island & 26 Dives

🌊 Dive Getaway – Puerto Galera, Philippines With NZDiver – May 2026 Join us for an unforgettable dive adventure in the Philippines!Discover the breathtaking reefs...

-

, by NZDiver Admin New Zealand Dive Clubs A Free Guide

"A helpful guide to choosing the right dive club in your area. Connect, learn, and dive deeper with your local community." Or a slightly more...

-

, by NZDiver Admin Motunau Beach Fishing Guide & Angler Etiquette

Finding a reliable Motunau fishing guide is the first step toward navigating one of the most technical river bar crossings in North Canterbury. Many boaties...

-

, by NZDiver Admin Chasing Kingfish on the Spear in Winter

Photos by Etoile SmuldersIt is generally accepted that the kingfish in NZ largely ‘disappear’ for the winter months. They typically head to an unknown destination...

-

, by NZDiver Admin How To Catch Snapper

Snapper is arguably New Zealand’s most popular sport and table fish. They are copper-pink on top with a silver-white underside and small blue dots along...